The Science Behind Autism and the 'Developmental Disorders': Tortuous or Tortured-Juniper Publishers

Global Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disabilities (GJIDD)

The history of coming to grips with what autism is

and its etiology has been tortuous -if not tortured. By 1908 the word

autism was defined as a schizophrenic who was withdrawn or

self-absorbed. Some decades later Leo Kannern [1]

decided that autism was based on children with "a powerful desire for

aloneness.” In the 1960's psychologist Bruno Bettelheim, picking up on

another aspect of Kanner's [2]

observations, thought autism was simply based upon mothers not loving

their children enough. Then came the twin research studies which

purported autism to be caused by genetics or biological differences in

brain development. Yet the consensus that Autism is from an intrauterine

infection had also been growing, bolstered more recently by Patterson's

[3] and Fatemi's [4]

studies. However, the question would still remain: which infection?

This, of course, remains unknown. Until 1980 autism in the US is still

called "childhood schizophrenia” and in some parts of the world, it

still is. By the same token, there has been, for some time, an extensive

body of medical literature which ties schizophrenia to chronic

infection -some time before when Rzhetsky [5]

in 2007, used a proof-of-concept bio-statistical analysis of 1.5

million patient records, finding significant genetic overlap in humans

with autism, schizophrenia and tuberculosis. Tracing the history of

autism from John Langdon Down's children, a subset of which were

autistic, to the present, this paper also explains how the stealth

pathogen hypothesized to be behind autism has evaded modern day

diagnostics.

Keywords: Autism; Autistic spectrum; Childhood schizophrenia; Asperger's disease; Etiology of autism; History of autism California Department of Developmental Services, Sacramento, 1999

California, in 1999, had been on high alert for some

time. Level one autism, without any of its "spectrum,” went from almost

five thousand cases in late summer 1993 to an estimated 20,377 cases by

December 2002. As California's Department of Developmental Services

stood by incredulously, it witnessed at rippling of California's autism

rate, and all but 15 percent of cases were in children.

California wasn't alone. But its autism rates had

become the fastest growing group in that state's developmental

disability system, and a number of Bay Area school districts were forced

to fill entire classes with youths with different forms of autism.

But even in the midst of California's mini-epidemic,

its Santa Clara County seemed particularly singled out. The Department

of Social Services Aid, brokered by the San Andreas Regional Center,

staggered to its breaking point, and its forecast for autism in Santa

Clara wasn't good.

What was behind this epidemic? A major clue,

overlooked from a critical stand point, was contained in the time line

of the department's own 1999 autism report, which concluded that the

disease had increased dramatically between 1987 and 1998.

What had happened in California in and around 1987 that could haves own the surplus of autism that California no wreaked?

Division of Communicable Diseases, Sacramento, California, 1999

While autism exploded in California, there was also,

beginning in 1987, a major spike in the number of tuberculosis cases

reported by the Tuberculosis Control Branch of California's Division of

Communicable Disease. There, division head Dr. Sarah Royce proclaimed a

TB epidemic in California. The epidemic peaked in1992, had the same male

preponderance as autism, and took off at precisely the same moment in

time.

California's TB epidemic might have already peaked

well before 1999, but this didn't stop it from continuing to contribute

the greatest number of cases to the nation's total tuberculosis

morbidity [6]. But, as with autism, the problem was worldwide, and even the World Health Organization, traditionally slow to

react, had declared a global tuberculosis emergency six years earlier, a warning that has been in existence ever since [7].

Among children, brain-seeking central nervous system

tuberculosis is common in a disease that kills more children each year

than any other, with the potential to cause in survivors, among other

things in its devastating wake, a withdrawal from social interaction [8].

It had to be more than a coincidence, therefore, that

since the 1980s, California experienced a dramatic increase in the

number of children diagnosed with autism as well [9].

Santa Clara County California, March 2006

If California was experiencing autistic rumors, then

surely its Santa Clara County was at the epicenter. By 2006, Santa Clara

had some of the highest rates for autism in the entire country And

although this was for unknown reasons, again the question became, why

Santa Clara? And the answer pointed in a similar direction. By 2002, it

had become apparent that TB was on the rise in Santa Clara, and, by

2006, that county had the highest number of new TB cases in

California-more than most US States. At the same time, the immigrant

share in Santa Clara County, mostly from countries where TB is endemic

was at its highest point since 1870. Santa Clara's Health Department

sounded the alarm. Santa Clara now knew that it had two problems on its

hands. Its medically trained psychiatrists, personnel and statisticians

just never stopped to think that the two problems might be related.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, September 2008

Time passed. More information came to in. In

September 2008, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published

a study by lead author, pediatrician, and researcher Laura J. Christie

of the California Department of Public Health entitled "Diagnostic

Challenges of Central Nervous System Tuberculosis.” Christie and

colleagues identified twenty cases of unexplained encephalitis referred

to the California Encephalitis Project that were indeed tubercular [10].

The team importantly began with the significant statement that

"Tuberculosis (TB) of the central nervous system (CNS)” as thought of by

physicians, "is classically described as meaning it is. However,

altered mental status, including encephalitis is within the spectrum of

clinical manifestations.”

Indeed, according to Seth and Kabra, central nervous

system tuberculosis in children canal so include tuberculous

vasculopathy (infection of cerebral blood vessels), small tubercular

masses called tuberculomas or TB abscesses [11].

In most of the twenty cases, the California

Encephalitis Project culture doubt tuberculosis, the same tuberculosis

considered the least likely cause for encephalitis. Yet there it was.

But, as Christie pointed out, as little as 25 percent of patients with a

diagnosis of CNSTB actually cultured out TB, which was a criteria for

this particular study That means that only %th of possible cases were

being diagnosed. And even the most sophisticated diagnostic lab tests

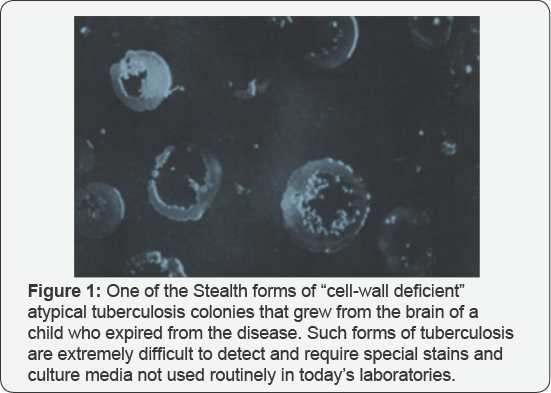

proved not helpful in further probing the culture proven cases (Figure 1).

Office of the Medical Superintendent, Earls Wood Asylum for Idiots, Surrey England, 1887

Figure 2

It was in the teachings of John Lang don Down, some of whose "mentally

retarded” children were autistic, that Leo Kanner really found his

autism. Down, one of the outstanding medical scholars of his day, was

certain to gain entrance into the prominent London Hospital when he

decided instead to pursue an avenue few would entertain, as super in ten

dent of the Earls wood Asylum for Idiots in Surrey. But for Down, it

was preordained. At the age of eighteen, he had what might be described

as a transformative experience. A heavy summer storm drove his family to

take shelter in a cottage. Down wrote: "I was brought into contact with

a fee blamed girl, who waited on our party and for whom the question

haunted me-could nothing for her be done? I had then not entered on a

medical student's career but ever and an on their membrane of that

hapless girl present edit self to mean longed to do something for her

kind”

[12].

Down, therefore, became a doctor for reasons that

were the purist of the mall, and he soon excelled and became the head of

his class. His pursuits were brought to a temporary halt when he

acquired tuberculosis, which sent him back to his family's home in Tor

point. Gradually, here covered. Down then went through an obstetrics

residency before obtaining his MD to assume the position of head of the

Earls wood Asylum. He was now quite knowledge able about pregnancy, the

complications and diseases of pregnancy, and neonates. In addition, his

surgical skills allow him to do autopsies, during which he contributes

much to expand knowledge of conditions of the brain such as cerebral

palsy as well as probe into what had killed the children in his

institution that died from Down syndrome.

In his Let sonian Lectures, Down follows the

psychiatric nomenclature of his time and classifies his most severe

cases of mental retardation in the young under the category of "idiocy”

[13]

. Like Kanner, he specifies that some of his mentally retarded children

had exceptional intellect in specific areas, such as memorization,

music, or mathematics. In fact, a noticeable subset of the autistic

children that Down treated did not appear physically to even have mental

retardation.

Gill berg & Coleman [14] relate that quite a number of reports of individuals with Down syndrome also meet the criteria for autism.

By 1867, John [15]

had appeared in the Lancet, linking childhood mental illness with

tuberculosis. To Down, in fact, children who inherited Down syndrome

"for the most part, arose from tuberculosis in the parents” and not

genetics [16]. Capone mentions that Down's original report attributed the condition to maternal tuberculosis [17].

As a result of such tuberculosis from conception or soon thereafter,

and nothing else, such children's life expectancy would be shortened, as

the same tuberculosis infection would lead to their early demise. The

only thing really wrong with John Langdon Down's theory was that it was

way ahead of its time. He knew that tuberculosis was, as it still is,

the most common cause of death from a single infectious agent in

children, now killing upwards of 250,000 children each year, yet

exceedingly difficult to diagnose [18-20].

He also knew that TB was the single leading cause of death among women

of reproductive age, between fifteen and forty-four, one million of whom

presently die, according to the World Health Organization, each year [21].

Brain and central nervous system tuberculosis account

for 20-45 percent of all types of tuberculosis among children, much

higher than its rate of 2.9 to 5.9 percent for all adult tuberculosis [22].

In fact, tuberculosis of the nervous system has consistently been the

second most common form of TB outside of the lung in the very young. And

of those infants and children who did survive, nearly 20 to 25 percent

manifested mental retardation and mental disorders-serious and long-term

behavioral

disturbances, seizures, and motor (movement) handicaps in addition to

the various other anomalies associated with the autistic spectrum and

what Down called "neuro developmental” behavior problems [23-25] (Figure 3).

Today, Down is considered wrong for saying that Down

syndrome was caused by parental tuberculosis and rather that it is a

"genetic” abnormality, a next a chromo some on Chromosome 21 called

trisomy. But was Done really wrong? To this day, no one has come up with

the actual cause for this genetic abnormality. This was probably why

the discoverer of the extra chromosome, Frenchman Jerome Lejeune,

hesitated to publish results that were otherwise clear- cut. And when

Lejeune faced McGill geneticists at a Montreal Congress of Genetics,

announcing that he had located an extra chromosome in the karyo type of

Down syndrome patients and showed it to them, he was received with

interest but skepticism considerable skepticism. Since, Warthin, Rao,

Lakimenko, and Golubchick have all revealed how tuberculosis itself can

cause chromosomal change reminiscent of those found in Lejeune's trisomy

[26-29].

Warth in showed tuberculosis's early penetration right into the corpus

luteum itself, in which 90 percent of Down syndrome's abnormal meiotic

chromosomal splitting occurs. Rao also found that the tubercle bacillus

is capable of inducing such chromosomal changes as result in Down

syndrome's non disjunction of the human egg. And Lakimenko et al. [30]

independently proved just how devastating TB could be to the

chromosomal apparatus of cell cultures of the human amnion, in tone, but

two independent studies. Each showed an increase in pathological

mitoses, arrest of cell division in metaphase, and the actual appearance

of chromosomal adhesions absent in control cultures. Indeed, Lakimenko

et al. [30]

demonstrated that early tubercular involvement was not only destructive

against chromosomes but the very spindles that separated them. Total

ovarian destruction occurs in 3 percent of women with pelvic

tuberculosis, against the site where Down syndrome's and autism's

chromosomal abnormalities usually occur[30].

For his Lancet study, Down submits one hundred post

mortem records of children who had passed away at his institution. He

had found no fewer than 62 percent of these children to have tubercular

deposits in their bodies. For some unknown reason, boys had more than

twice the incidence of tubercles in their organs as did girls, a finding

that concurred with the male predominance he later notes in childhood

mental disease in general. Such male preponderance is today not only

documented in Down syndrome but in autism as well. Tuberculosis is might

be more frequently transmitted by the mother than the father, but it

was the male offspring who were more tubercular. Caldecott, in a 1909

British Medical Journal article, noted that Down showed that the

children in his study rarely lived beyond twenty years as a consequence

of brain and nervous system disease, and that they died of tuberculosis [31].

Department of of Psychiatry, Burgholzli Hospital, Zurich, Switzerland, 1930

Figure 4

The word autism first appeared in English in the April 1913 issue of

the American Journal of Insanity, heralded at an address that Swiss

psychiatrist Paul Eugen Bleulerde livered for the opening of Johns

Hopkins University's Henry Phipps Psychiatric Clinic [32].

Bleuler used the word autism, Greek for "self,” to

describe the difficulty that people with schizophrenia experience

connecting with other people, and, in certain cases, with drawing into

their own world and showing self-centered thought. But to Bleuler,

schizophrenia, and there by autism, still came from an organic cause

such as infection, and, as such, was sometimes curable. Until about

1980, autism and schizophrenia were considered basically one and the

same. To that point, Bleuler's definition holds.

Bleuler also uses autistic to describe doctors who

are not attached to scientific reality, wont to build on what Bleuler

calls "autistic ways” that is, through methods in no way supported by

scientific evidence, an event more and more in evidence as psychiatrists

moved away from tissue-based out comes into the realm of subjective

behavioral belling. The history of autism would seem any such

individuals. "Bleuler used the word autism, Greek for "self,” to

describe the difficulty that people with schizophrenia experience

reconnecting with other people, and, in certain cases, withdrawing into

their own world and showing self-centered thought.”

Child Psychiatry Service, Johns Hopkins University Hospital, Pediatric Division, Baltimore,1933

Internal-medicine trained Leo Kanner [1]

teaches himself the basics of child psychiatry and, at the instigation

of Adolph Meyer, joins the Henry Phipps Psychiatric Clinic at John

Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.

By 1903, Henry Phipps, wealthy partner of Andrew

Carnegie, sought charitable outlets for his wealth. He then joined

Lawrence F Flick, a doctor with a vision, to open a center solely

dedicated to the study, treatment ,and prevention of tuberculosis, hands

down the number one infectious killer in the United States.

Figure 5

Not until May 1908 did Philadelphia steel magnate Phipps get around to

visiting Johns Hopkins's tuberculosis division, which he had funded. At

that point Phipps turns to ask John Hopkins's dean and legendary

pathologist William Henry Welche if he needed help sponsoring other

projects at the Hospital. Welch answers Phipps by handing him a copy of A

Mind that found itself, an agonizing assessment of mental asylums

written by Clifford W Beers and published with the help of Swiss born

pathologist Adolph Meyer [33].

Within a month, Phipps agrees to donate $1.5 million to fund a

psychiatric clinic for the Johns Hopkins Department of Psychiatry. By

1912, the Henry Phipps Psychiatric Service at Johns Hopkins Hospital

provides the first in-patient psychiatric facility in the United States

for the mentally ill. Welch likes Meyer. Meyer, although unable to

secure an appointment from his all matter, the University of Zurich, is,

like Welch, a pathologist a neuropathologist to be exact. Also Welch

takes to him because Meyer initially seems to reject Freud as the be-all

and end-all for psychiatry. And there is another level of

understanding: Meyer and Welch share the rapport of two superb medical

networkers and politicians. Welch sees to it that Meyer becomes the head

of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins.

But it is the very same second-rate, vague,

"psychobiological” views that characterize Meyer's psychiatric approach

that will prove in the end to be disappointing. Designed to be all

things to all people, Meyer's psychobiology assesses mental patients’

physical and psychosocial problems concomitantly, but turns out to be

all things to no one. Meyer is much more oriented towards taking

extensive histories of his patients; getting all the "facts”, then in

rooting out the pathology behind mental illness son the autopsy table.

Besides, the positions of Meyer and Freud closely resemble one another

in that each insists heavily on the study of psychogenic factors in

neurotic disorders. Welch, on the other hand, was committed to bringing

the German model, which relied heavily on the lab, to US medicine. So

with Meyer, Welch didn't precisely get what he thought he was getting.

Nevertheless, thanks to neurologist and pathologist Adolph Meyer, Leo Kanner [1]

becomes the first "child psychiatrist” at Johns Hopkins and, by

default, in the United States. Meyer is Benton changing American

psychiatry, and will dominate psychiatry from his Johns Hopkins chair

during the first half of the twentieth century. Meyer has long been

interested in the psychiatric treatment of children, so hear ranges with

Johns Hopkins pediatrician Edwards Park for Kanner to become aliasion

between pediatrics and psychiatry at the institution. This gives Kanner

enhanced influence in reaching an audience of pediatricians who

otherwise would have found little value in the psychiatric evaluation of

children. Meyer has already decided that the psychosocial aspects of

mental disease are more important than tissue diagnosis of brain

pathology. He closes his laboratory, and instead prefers talking to his

patients, taking extensive histories in the manner of Kraepelin and

Sigmund Freud.

Child psychiatry service, Johns Hopkins University Hospital, Pediatric Division, Baltimore,1934

(Figure 6)

Kanner, with little use for medical diagnostics himself, seems made to

order for Meyer. Kanner will and Meyer for shifting the emphasis of

psychiatry "from organs and their diseases to patients as improperly

functioning persons [34].”

But diseased organs can themselves lead to improperly functioning

persons. Kanner never really seemed that interested in "organs and their

diseases”. While still in Berlin finishing his medical education, his

lowest grade on his finals is as the result of being unable to diagnosis

the then premier infectious brain disorder leading to mental symptoms.

Neurologist Karl Bonhoeffer documents that Kanner misinterpreted the

symptoms of tabesdorsalis, a neurologic end-stage syphilis of the brain

and nervous system [1].

Not really attracted to being a general internist, and still in Berlin,

Kanner gravitates into the then new and relatively limited field of

electrocardiography, or EKG tracings of the heart's rhythms. Once at

Johns Hopkins, Kanner writes his first edition of Child Psychiatry in

1935, borrowing the name from the German term Kinder psychiatric. And by

1943, bent upon making his mark, he discovers a "new” syndrome. Without

mention of Bleuler, who originated the word "autism”, Kanner use sit to

describe what he feels to be a novel psychiatric illness in children,

emphasizing an "autistic aloneness” and "insistence on sameness.”

Ironically, Kanner, known to rant and rage over mere psychiatric labels

without treatment, creates another one: autism.

Office of the Director, Department of Medical Genetics, New York State Psychiatric Institute, July 1936

(Figure 7)

Leo Kanner and Franz J Kallmann had a couple of things in common. Both

had connections with the University of Berlin. Kallmann worked for four

years at Berlin's psychiatric institute under the same Karl Fried rich

Bonho effer who graded a portion of Kanner's final exams. Although

Kanner is only three years older than Kallmann, and Kanner is trained in

internal medicine, both would move quickly upon their arrival to the

United States to make their impact on psychiatry Landing in New York,

Kallmann establishes the Medical Genetics Department of the New York

State Psychiatric Institute. From the no, one thing is certain: With

Franz J Kallmann, American psychiatry got much more of the hereditary

patterns in mental disease than it was willing to accept or pursue.

Prominent British geneticist Penrose judged Kallmann's work

unconvincing. A year after Kanner writes Child Psychiatry, Kallmann

becomes interested in twins and their genetic disposition. But there

arises an inconvenient truth: Identical twins, who have virtually the

same DNA, do not always develop the same mental disorders. Kallmann

focuses on what he calls the "genetics of schizophrenia.” In a lecture,

he finds it desirable to prevent their production of relatives of

patients with schizophrenia. He defines them as undesirable from

aeugenic point of view, especially at the beginning of their

reproductive years. By 1938, Kallmann, who escaped Nazi Germany because

he was half Jewish, has doubled down, calling for the "legal power” to

sterilize "tainted children and siblings of schizophrenics” and to

prevent marriages involving "schizoideccentrics and border line

cases.”In his mind, Kallmann feels the need to stamp out every recessive

gene behind schizophrenia [35].

It was a thought that began incubating in him while he was still in

Germany LeoKanner is appalled by Kallmann's thoughts and words. He sees

dangerous implications. This time he is correct. Kallmann is a zeal at

in every sense of the world. He finds a genetic basis for just about

everything. He proclaims that human tuberculosis is genetically based.

His age is doing so is quite transparent. Proponents like Kallmann for a

"genetic” or "hereditary” view of mental illness have always relied on

identical twin studies. In these, if there is a heavy degree of

"concordance”-meaning that if both identical twins comedown with the

illness-it is supposed that "genetic” influences are involved. This is

so, especially if at the same time fraternal twins show a much lower

rate in being "concordant for”-or contracting-the same disease. But it

was also known that an infectious disease like tuberculosis brought in

the same numbers in identical twin studies as did schizophrenia or

autism, putting the accuracy of such twin studies deeply in question. In

fact, it was Kallmann himself who found that approximately 85percent of

identical (homozygous) twins had the same disease (were concordant) if

their co-twin had either tuberculosis or schizophrenia [36,37].

Kallmann's study for the hereditary basis of schizophrenia is published

in 1938. It acknowledges his long-time boss and Nazi mentor Ernst Rudin

[38].

While still in Germany, Kallmann saw Rude in catapulated to director of

the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Psychiatry and it's eugenics division

through Rockefeller Foundation money, creating the medical specialty

known as psychiatric genetics.

Rudin was not only assisted by Kallmann but another proto gene named

Otmar Verschuer. Back in Germany, Rudin, a year later, sees to it that

the German version of Kallmann's book is used by the NaziT4 Unitasa blue

print for the murder of mental patients and "defectives,” many of them

children. 250,000 are killed under this program, by gas and lethal

injection. The Rockefeller-Rudin operation had become a section of the

Nazi state. Rudin was now head of its Racial Hygiene Society. Mean

while, in the United States, geneticist Franz Kallmann becomes an early

leader of the American Society of Human Genetics, a true pioneer in the

study of the genetic basis of psychiatric disorders. Kallmann's American

Society of Human Genetics organizes the Human Genome Project. The most

ambitious project ever dealing with basic genetics. In 1988, Congress

provides funds for the National Institutes of Health and other groups to

begin mapping out human DNA. The project began officially on Octoberl,

1990, with a projected budget of $3billion over the next fifteen years.

As BW Richards points out, advances regarding the discovery of genetic

markers for diseases such as autism, Down syndrome, and schizophrenia,

although good for diagnostics, have done little to get at the actual

cause of such chromosomal aberrations. Richards: "Despite dramatic

advances in the fields of biochemistry and cyto genetics, revealing many

new causes of mental retardation, a large proportion of mentally

retarded patients are still un diagnosable in respect of etiology

(cause)”[39].

What did result, thanks to such take-no prisoners actions like

Kallmann's, was that bacteriology was purposely confined to a special it

of medicine outside the schools of biology, botany, and zoology, in no

small part responsible for bacteriology's slow acceptance.

Bacteriologists, in retaliation, steered clear and gave no credence to

any of the proclamations of geneticists. Unbelievably, the situation had

gotten so out of hand that, as late as 1945, bacteriologist Rene Dubos,

discoverer of the first Antibiotic ever, had to muster all of the

courage in him to name his mile stone paper "The Bacterial Cell.” Such

are and always have been the politics of medicine.

Office of the Director of Child Psychiatry, John Shopkins Hospital, Baltimore, 1943

(Figure 8)

To make certain that his theory sticks, Kanner cherry-picks eleven

children, leaving out those presently with seizures or mental

retardation even though these are very much in today's autistic

spectrum. Some studies have mental retardation occurring in

approximately two-thirds of individuals with autism and seizures in

approximately one-third.

Kanner produces a thirty-three-page medically sketchy paper [2].

He outlines eleven case histories, all the while convincing himself

that, despite findings such as a history of seizures, which could point

to a brush with serious disease, his subjects' problems were purely

psychiatric or behavioral. At the same time he says that, unlike

childhood schizophrenia, autism is the result of "inborn autistic

disturbances of affective contact”-a kind of congenital lack of interest

in other people. Yet most of his children are thought to be deaf,

neither talking nor responding if questioned, and could have severe

cranial nerve disruption from a previous or present serious central

nervous system infection. "Physically,” Kanner insists, despite findings

that suggest otherwise, "the children were essentially normal.” But

five out of his eleven subjects, through measurement "had relatively

large heads,” which could indicate possible degrees of hydrocephalous.

Hydrocephalous, also known as "water on the brain,” is a medical

condition in which there is an abnormal accumulation of cerebro spinal

fluid in the ventricles, or deep cavities, in the brain. This may cause

increased intracranial pressure inside the skull and progressive

enlargement of the head, seizures, and mental disability. Not uncommon,

one of its causes in infants is perinatal infection affecting the brain

and nervous system. At one time, the diagnosis of acute hydrocephalus

was so commonly associated with tuberculosis meningitis that the terms

were used interchangeably. But apparently of more concern to Kanner were

the children's parents: "In the whole group, there are very few really

warm hearted father's or mother's.” Kanner in general felt that

disturbed children often were the product of parents who were highly

organized, rational, and cold, "just happening to defrost enough to have

a child” [40].

When, in his first case, Kanner finds out through DonaldT. Mother that

the child had been placed in a "tuberculosis preventorium” for "a change

of environment,” Kanner never questions her as to why, but notes that

while in the tuberculosis preventorium, he exhibited a "disinclination

to play with children. ”Kanner will later relate that "the mother gave

Donald little attention because "she feared he would give her

tuberculosis” and casually dismisses this by adding, "which he did not

have” [41].

But in order to be sent to a preventorium, Donald T. Must have had a

positive TB skin test, which was not mentioned; nor was it mentioned

what other tests were performed to rule out that the child did indeed

not have tuberculosis.

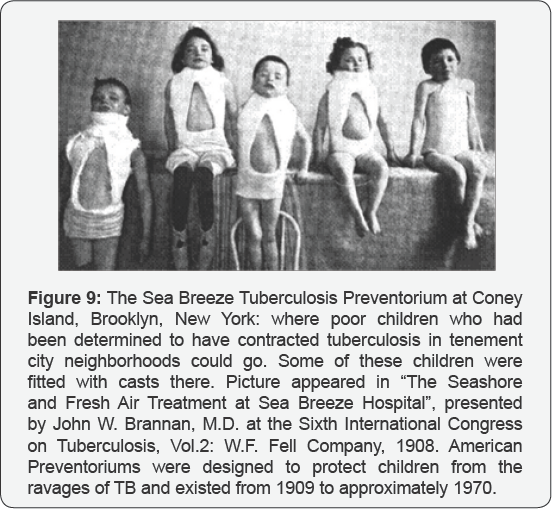

Figure 9

all but forgotten, tuberculosis preventoriums were America's answer to

preventing tuberculosis epidemics among the urban poor. This was

accomplished by ripping "pretubercular” children from their homes and

placing the mint of residential institutions [42].

From the beginning of the twentieth century and well into it, such

primitive "preventoriums” were seen as the only solution to break the

chain in a disease that, by 1900, had killed at least 15 percent of

urban populations, with no treatment in sight. By 1907, von Pirquet came

up with a children's tuberculin skin test with all the flaws of our

present adult tuberculin skin test. Not only were false negative tests

done on seriously infected children whose immune systems could simply

not muster a positive skin reaction, but even when the test proved

positive, it was often impossible to distinguish mere previous exposure

from active disease. Nevertheless, the imprecise designation "pre

tubercular” was used to designate children with positive skin tests who

didn't seem to have active disease. These were the children targeted for

preventoriums. Kanner knows from the onset that his definition of

"autism” will be challenged, on many levels. Even among psychiatrists

presented with these same children, responses would include mentally

retarded or schizophrenic. The fact was that, psychiatrically, all would

be considered by many as having a form of childhood schizophrenia. To

make the differentiation stick, Kanner emphasizes "extreme solitude from

the very beginning of life” and a preserved intelligence. But many of

the developmentally disabled children that Down had studied had normal

intelligence also and certainly did not appear to have mental

retardation [43].

Kanner argues that the children in his study, unlike schizophrenics,

did not seem to have elusions or hallucinations. In addition, he says,

schizophrenia doesn't emerge in as early as the thirty months after

birth that autism seemed to. But more tellingly, in 1949, Kanner

vacillates, admitting that he sees none for his "infantile autism” to be

separated from schizophrenia [2].

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) balks in accommodation and

decades later still won't acknowledge autism as anything other than just

that: "schizophrenia, childhood type.” [44] By then, Kanner deplores the APA's decision [1]. Yet despite this, until 1980, Kanner's autism is not autism; it is childhood schizophrenia [45].

One year after the APA's 1968 decision, prominent Bellevue child

psychiatrist Lauretta Benderargues that children with autism generally

grow up to have schizophrenia any way. And on top of that, despite the

ever-increasing rallying cry by American psychiatric guru's as to

childhood schizophrenia's extreme rarity, Bender documents thousands of

cases of it while at Bellevue [46].

German psychiatry, which long maintained its influence over Europe, and

the Soviet and Eastern Bloc countries also insisted that childhood

autism is the initial form of schizophrenia, with development into

schizophrenia more or less in evitable. Moreover, some in the field

understood that clear and unmistakable evidence of the autistic disorder

could be found in J Langdon Down's 1887 "developmental” form of mental

retardation, which Down attributed mostly to tuberculosis in the child's

parents [13,16]. The stage was set for a battle royal.

Johns Hopkins Department of Pathology, Baltimore, 1946

Though his office was but a short distance away from

Leo Kanner's, Johns Hopkins TB pathologist Arnold Rich lived in a

completely different world. In Rich's world, there were no psychiatric

hypotheticals, no diagnoses not verifiable by laboratory reagents and

microscopic findings.

Figure 10

Although it appeared that Rich and Kanner worked in completely

different arenas, at times they unknowingly touched directly on one

another's work, but never more closely than when Rich began to focus on

perinatal infectious disease. Rich was a teaching dynamo at Johns

Hopkins, completing his authoritative Pathogenesis of Tuberculosis in

1944, with a second edition in 1951 [47]. It took him nine years to compile and still remains a model of what a scientific monograph should be.

By virtue of his astute powers of observation, Rich

had always stood out from the rest, even at Johns Hopkins. His name

remains on the lung condition called Hamman-Rich syndrome, and the small

tuberculousmasses (tuberculomas) that metastasized, not in frequently,

to, among other areas, the human brain, and became immortalized as

"Rich's foci”. He was also the first to describe the high prevalence of

occult prostate cancer in elderly men as well as the first to describe

wide spread vascular obstruction in the lungs in children with the

hereditary heart condition called Tetralogy of Fallot.

During Rich's tenure, much as in the past, the

prevailing emphasis at Johns Hopkins laboratory research was either with

the living or recently deceased, but the way in which Phipps psychiatry

under Meyer neglected it's bench work research gave it a somewhat

remote character to the rest of Johns Hopkins, preventing closer

association. In addition, it seemed that Meyer's protege, Leo Kanner was

looking only at the very tip of the same iceberg that John Langdon Down

had come to grips with so long ago. When Kanner spoke of an "inborn”

condition affecting mentation, Rich, as well as Down previously, had

afairly good idea of what he was speaking about, and to Rich it was no

more a condition caused by heredity than the nonsensical documents that

crossed his desk weekly claiming human TB to be hereditary or caused by

the wrong genes. Rich, like Down, knew that TB was the most common cause

of death from a single infectious agent in young children and neonates,

commonly attacking their central nervous system [18, 48].

The Germans had their own name for childhood tuberculosis, kinder

tuberculose, and in the many children who survived, besides leaving

their tiny bodies gnarled, nearly 20 to 2 5 percent manifested mental

retardation and psychiatric disorders [23].

And for various reasons, many did survive-leaving in its wake, among

other conditions -Down syndrome, the autistic and the 'mentally

disabled'. So until this significant pool of infected neonates, infants,

and toddlers was fully evaluated for such protean mental complications,

Arnold Rich truly couldn't understand psychiatrist's fussing over

"inborn” features of a "psychiatric” disease, whether labeled autism or

anything else that very possibly was caused by organic infection. It

just didn't make sense. A neurologist friend had confided in Rich that

Kanner's autism seemed more like a disease caused by post-encephalitic

phenomena than anything else. Rich knew that tuberculosis was fully

capable of causing such an encephalitis, described by one pediatric

infectious disease specialist as being indolent or slow to develop and

heal, often as painlessly as any other central nervous infection around [49].

Figure 11

Rich looked up at the picture of William Henry Welch (1850-1934). Welch

had been both Rich's predecessor at Hopkins Department of Pathology, as

well as dean of medicine and founder of the Johns Hopkins University

Medical School. Welch was unique. Welch was different. He was an over

and a shaker, an organizational genius who would single-handedly force

US medicine up to and eventually beyond what they had in Europe. A

bacteriologist and a pathologist, Welch would one day be called the dean

of American medicine. During his watch American life expectancy would

jump by at least twenty years. And William Henry Welch would be a major

factor in that leap.

Rich looked up at the picture of William Henry Welch (1850-1934). (Figure 11)

Welch had been both Rich's predecessor at Hopkins Department of

Pathology, as well as Dean of Medicine and founder of the Johns Hopkins

University Medical School. Welch was unique. Welch was different. He was

an mover and a shaker, an organizational genius who would

single-handedly force US medicine up to and eventually beyond what day

be called "the Dean of American medicine" During his watch American life

expectancy would jump by at least twenty years And William Henry Welch

would be a major factor in that leap.

Rich was proud both of the association and to have

personally known the physician considered both the father of American

medicine and one of its most influential members. Welch had studied in

Germany under the great masters, including stints with Koch, Cohnheim,

and psychiatrist and neurologist Meynert. Welch therefore well realized

the importance of seeking out diseased tissue in the mentally ill.

Meynert decried those like Kraepelin and Meyer, who Seemed preoccupied

with labeling symptoms instead of going after the real tissue cause of

brain or central nervous system illness [50].

And having also worked with Koch, Welch held a keen appreciation for

the destruction, both inside and outside of the mind, that tuberculosis

could cause. With regard to the immediate problem in front of him, Rich

had read Knoph's review in which he said of Welch that "He too was of

the opinion that a direct bacillary transmission, that is to say,

prenatal infection (with tuberculosis), takes place much more frequently

than believed”[51].

Like Rich, Knoph also knew that few fetal autopsies

and exhaustive studies were done to prove fatal tuberculosis on dead

fetuses. And those studies had to contend with the fact that

tuberculosis, a microbe that grew only with sufficient oxygen, was most

often impossible to isolate in the low-oxygen content of fetal blood or

tissue. It's not that TB had any trouble surviving under low-oxygen

conditions; it just did so in undetectable dormant forms, causing a

diagnostic night mare. Rich questioned the wisdom of Welch in choosing

someone like Adolph Meyer to run Hopkins's psychiatry. Meyer seemed such

a far cry from Johns Hopkins neurologist D.J. Mc Carthy, previously on

staff at Phipps Tuberculosis and an authority on tuberculosis of the

nervous system in infants and children [52].

McCarthy knew not only that cerebral tuberculosis occurred with much

greater frequency in infancy and childhood than most realized, but

reported a distinct and causative relationship between tuberculosis and

adolescent schizophrenia itself. In fact, McCarthy's investigation at

Johns Hopkins Phipps Tuberculous Pavilion for the mentally ill revealed

that practically all of the patients isolated there had schizophrenia.

This seemed particularly relevant when taken in light of Lauretta

Bender's argument that children with autism generally grow up to have

schizophrenia anyway [46].

McCarthy was far from the first investigator to link schizophrenia with

TB. Although eventually the term childhood schizophrenia was displaced

altogether regarding autism, there remained those children who displayed

both the early-appearing social and communicative characteristic of

autism and the emotional instability and disordered thought processes

that resembled schizophrenia. Rich wondered if either Kanner or Meyer

had as extensive a knowledge of the infectious orientation of German

psychiatry as did pathologist William Henry Welch, who once walked with

its giants.

Psychiatric Asylums on the European and American Continents, Late Nineteenth Century

When Johns Hopkins pathologist William Henry Welch

studied under psychiatrist Meynert, it was in the late nineteenth

century, a time off earth at tuberculosis would destroy the entire

civilization of Europe. It was also when the first massive increase in

psychiatric illness and confinement to mental asylums occurred [53].

And although there was a sociological shift of patients going from

family care and poor houses to asylums, this in itself could not account

for the inexorable increase in asylum census. To distinguished

psychiatrist and writer E. Fuller Torrey, severe psychiatric illnesses

such as schizophrenia were comparatively new diseases, less than 250

years old, the confinement for which, even as a college student,

reminded Torrey of the tuberculosis sanitariums of a slightly earlier

era [54].

During this time frame, there was no autism as understood by Kanner,

just the autism Bleuler used to describe schizophrenia. Nor was there

the capacity to do a proof-of-concept bio-statistical analysis showing

significant genetic overlap in humans with autism, schizophrenia and

tuberculosis. Rather autism and schizophrenia were simply considered as

one with infectious concepts brought forward still being revisited by

various author's today [5,55].

In nineteenth- century asylums, the upward spiral became obvious. By

1884, in Germany, Karl Kahlbaum, perhaps the most under rated

psychiatrist in history and the true originator of US outcome- based

psychiatric classification, first described schizophrenia as a separate

entity. Kahlbaum: "It must be the experience of all psychiatric

institutions that the number of youthful patients has recently undergone

a considerable increase” [56].

It was between 1700 and 1900, that tuberculosis was responsible for the

deaths of approximately one billion (one thousand million) human

beings. The annual death rate from TB when Koch discovered its cause was

an incredible seven million people per year. There were others who also

saw this nineteenth-century grounds well of mental illness as

representing something new, including auditory hallucinations, as never

witnessed before.

Historians like Hare and Wilkins, among others, point out that it was

only then that schizophrenia, with its hallucinations and delusions, was

really even mentioned, representing no small part of the

late-nineteenth-century psychiatric flare ups [57,58].

Almost unheard of in the medical literature before this, chronic

delusions and hallucinations-such as hearing voices-became common in

asylum admissions at the same time Clouston, by 1892, was documenting

them in mental illness as a result of a killer pandemic of tuberculosis [59].

Max Jacobi, the originator of the school of thought that held that

infectious illness led to mental illness, was the first to a scribe

characteristic symptoms for this associated with tuberculosis [60].

Just as autism was thought to be a disease of "affect” or emotion by

Kanner, Jacobi in particular considered an unpredictable, emotional

(affective) change ability as characteristic of, and at times even

diagnostic for, latent, undiagnosed TB. Incredibly, Grading found

pulmonary tuberculosis during autopsy in 70 percent of mental defectives

and in 50 percent of the mentally affected with seizure disorders [61]. Seizures, not uncommon in autism, occurring 20 to 30 percent of its patients based on the majority of studies [62].

Barr spoke about the relationship between tuberculosis and mental

defectiveness at the Sixth International Tuberculosis Congress held in

Washington, DC, in 1908 [63].

There, Jacques More expressed his belief that epilepsy and the

convulsive disorders were derived from tuberculosis. A year previously,

An glade spoke not only on how tuberculosis caused epilepsy in infants

and the young, but how such epileptics eventually became mentally

defective through sclerotic brain changes caused by the disease [64].

Subsequently, Baruk discovered that when either proteins extracted from

tuberculosis or the spinal fluid taken from people with schizophrenia

were introduced into healthy animals, a condition called catalepsy

occurred, in which the body and its functions seemed frozen in time.

Catalepsy is associated not only with one form of schizophrenia but with

epilepsy itself [65].

Patients with catatonia, an extreme form of withdrawal in which the

individual retreats into a completely immobile state, can also exhibit

catalepsy. Wing related in 2000 that the incidence of catatonia could be

as high as 17 percent in adolescents with autism [66].

Historically prominent Viennese pathologist Ernst Lowen stein decided

to take things a step beyond. Having developed a potato flour-and

egg-based tuberculosis growth media, still in use today, he set about to

prove that TB could be cultured from the blood of patients with

schizophrenia [67].

Yet despite nine independent confirmative studies finding either the

tuberculosis bacillus itself or it's much harder to stain yet more

common viral forms, other studies couldn't confirm these results.

Whether this was from defective laboratory procedure or from the

difficulty in staining and culturing viral (or cell-wall- deficient

forms) of tuberculosis remains, to this day, unknown. What is known is

that undeterred and in answer to these negative studies, Weeber, Melgar,

and Löwen stein again found tuberculosis in the blood of schizophrenic

patients-findings which, to this day, remain un addressed [68-70].

As far back as 1769, Scots man Robert Whytt, reporting on approximately

twenty cases, described the localization of tuberculosis in the

meninges, membranes that cover the brain and spinal cord [71].

Realizing that the localization of tuberculosis there was often

associated with mental disturbances, Whytt gave us the first description

of tuberculous meningitis, at that time called morbuscerebralis

Whyttii. In describing the disease, Whytt noticed not only small masses

called "tubercles” in the brain tissue but hydrocephalus, an excess of

"water in the brain.”A duct system circulates fluid in the brain and

spinal cord. The meninges that cover the brain manufacture and contain a

cerebro spinal fluid that circulates through channels of deep cisterns

in the brain and then down the spinal cord and back to the brain. A

block in this circulation, whether from a congenital condition or

disease, can lead to an increase of cerebrospinal fluid around the

brain. In infants and young children, because the bones of their skulls

are still unfused, this can result in an enlargement of the head. No

matter the age, mental disturbances and even retardation can result as

complications of such hydrocephalus. So inter twined was hydrocephalus

with tuberculosis that medical experts by the end of the nineteenth

century considered acute hydrocephalus as just another name for

tuberculous meningitis [72].

Since 1854, Wunderlich recognized that psychotic episodes, including

schizophrenia, could be caused by small masses of tuberculosis

(tubercles) in the brain [73].

But only as time passed, did it became more obvious just how commonly

this occurs. The tubercles of tuberculosis, which often form masses

called tuberculomas, are launched through the blood stream to the brain

and are often found in infants and adults with no neurologic symptoms.

But Marie documented symptomatic cases of tubercles as a cause of

psychosis such as schizophrenia [74].

TB meningitis was just the tip of the iceberg, and other investigators,

as early as 1908, uncovered a more generalized inflammation of the

brain matter, tuberculous encephalitis, "as also being behind specific

psychosis [75]. So the term tuberculous meningo encephalitis was considered more accurate than just tuberculous meningitis.

Department of Pathology Johns Hopkins, 1948

Arnold Rich was working on a problem that might have

major implications toward Kanner's child psychiatry, but he was having a

problem with regard to the frequency of maternal-to-fetal transfer of

tuberculosis [47].

It was also an issue with seminal significance in addressing Downs

develop mental disorders, of which autism was a division. In fact, it

was a topic that had been addressed by some of the greatest minds in

medicine. On the one hand, Rich knew that "It is now well established

that tuberculous infection can be transmitted from mother to fetus

through the placenta.” He references Warthin, who in an article in the

Journal of Infectious Diseases, said it was common, and Siegel's study

in the American Review of Tuberculosis [26,76].

Siegel documented infants that had died from the disease, one or two

days after birth. Husted's study even included tubercular still birth [77].

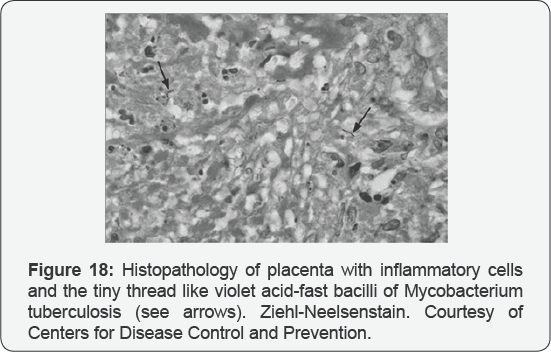

Figure 12

But to further establish the importance of a link between maternal and

perinatal tuberculosis, Arnold Rich felt the need to go into the numbers

involved in the general population. Of all the infectious diseases, TB

was and always had been a disease of alarmingly large numbers. Ever

since Norris's original review, it had been known that, for some reason,

pregnancy, especially late pregnancy, and child bearing itself

dangerously re-animated any form of tuberculosis in a woman's body, no

matter how silent [78].

Even latent TB with no symptoms, Norris mentions, could reactivate,

percolating TB bacilli in to the maternal blood stream for transfer into

the fetus. Thus, in the first half of the twentieth century, the method

of choice for an expectant mother with proven TB was early termination

of pregnancy [79].

Menstruation itself had a similar deleterious effect, causing its own

flare up of tuberculosis in the body. The numbers in front of Rich were

incredible.

In a disease that, according to the World Health

Organization, consistently kills more women of child bearing age than

any other, the age at which female tuberculosis mortality began to rise

above male mortality coincided with the average age of the onset of

menstruation. But the age at which the rate of tuberculosis mortality

really surpassed that of males coincided with the period during which

over two-thirds of all pregnancies occurred. Rich conservatively

estimated that a little over two million women between the ages of

eighteen and thirty were pregnant in 1940. And since the total US

population for women of this age was approximately 17.7 million, it

followed that one out of every eight women in the United States was

pregnant in this age range, and one in ten bore living children. This

not only produced a pool of 200,000 opportunities to re animated and

often undiagnosed maternal tuberculosis, with its drastically increased

female mortality rate, but, with such reactivation, the possibility for

the transmission of that disease to the fetus and newborn. In such are

animation of latent tuberculosis, it was also striking that TB

meningitis-which is in frequent in adults but frequent in infants and

toddlers-seemed to also noticeably increase in childbearing women from

there activation of old deposits of cerebral tuberculosis [80].

Rich already realized that, regarding TB's fatality in neonates,

infants, and young children, there was a definite pattern. Tuberculosis

was most fatal during the first year or two of life. After the second

year, the death rate for infected toddlers fell markedly, probably

through a greater ability to form protective antibodies between the ages

of two and five than during infancy [81].

Though the disease was still deadly for the remainder of the first five

years, by far the safest period was between five years and puberty,

when the death rate from TB plummeted. Often termed the "golden age of

resistance,” for some reason, children between ages five and fifteen are

more resistant to TB than adults and infants. It was an interesting

fact, creating a possible theoretical under pinning for Bender's

assertion as to how autistic involvement in the very young, hardest hit

in the first thirty months, could come back as a related schizophrenia

during adolescence, toward the end of the period of remarkable

resistance to the disease. It was thought at one time that newborns were

completely devoid of resistance to tuberculosis [82].

But sufficient studies had since contradicted this notion. In Brailey's

study at Rich's own Johns Hopkins Hospital, of sixty- five infants who

became tuberculin positive during the first year of life, two-thirds

were alive and well at the end of five years [83].

So the acquisition of tuberculosis by infants was not necessarily a

death sentence. However, its complications, including those involving

the brain and nervous system, could soon impact the individual for the

rest of his or her life. As to whether a notun common tuberculous focus

in the brain killed, Rich would soon find, was a matter of what he could

only refer accurately to as what card players know as 'the luck of the

draw'. It is not generally appreciated that the development of small,

rounded nodules caused by tuberculosis, sometimes cheesy or "caseous” in

the brain, is a relatively common occurrence in children and childhood

tuberculosis. It is usually symptom less. Such small nodules often

become arrested and encapsulated by the body's immune system. They are,

to this day, called Rich's foci. Many of us unknowingly have them. But,

stressed Rich, it is when small tubercle nodules happen to land in that

part of the surface of the cerebral cortex ear the meninges (covering of

the brain),no matter how small, that serious troubles began. Such

infectious nodules often extended into this protective covering through

which cerebro spinal fluid percolates on its journey through the brain

and into the spine. Such a discharge of tuberculosis into the spinal

fluid of the meninges (in its subarachnoid space) can (and often does)

lead to potentially fatal meningitis. The disease festers and spreads

throughout the central nervous system. There need not be extensive

infection, just one tiny nodule in the wrong place, near the meninges.

On the other hand, the development of small tubercles deeper in the

brain substance, though relatively common, often gave rise to no

symptoms what so ever. Rich himself had seen one-inch tuberculous masses

lodged in a silent area of the brain that were seemingly entirely

harmless. As ever hypersensitivity reaction to just the tuberculo

protein thrown of fin even a dormant tubercular infection could also

occur in any tissue in the body, including the brain, in infants already

hyper sensitized to tuberculous protein while in their mother's womb.

Burnand Finley showed damage and death of cells as well as acute

inflammation in the meninges in such instances [84].

The inflammation that resulted required no TB bacilli, just the

sustained diffusion of the protein of the tuberculosis bacilli or its

active split products through the placenta into a previously sensitized

infant.

Through it all, one thing was certain: Tuberculosis

did not always kill. That infants could survive even a massive dose of

tuberculosis was amply demonstrated in the tragedy called the Lubeck

episode [85].

In the German city of Lubeck, of 251 infants mistakenly injected with

large numbers of virulent human tubercular bacilli, in correctly thought

to be the TB vaccination called BCG, 71.3 percent survived.

But the number of possible complications in those

infants and children who survived TB's on slaught, including those to

the brain and nervous system, Rich knew, would be enough to keep

symptom-based psychiatry perturb bed and under siege for some time to

come.

University of Pennsylvania Department Of Psychology, 1949

But psychiatry was already under siege. In 1949,

psychologist Philip Ash, in a University of Pennsylvania post doctoral

dissertation, proved that three psychiatrists faced with a single

patient and given identical information at the same moment in time were

able to reach the same diagnostic conclusion only about 20 percent of

the time [86].

Subsequently, Aaron T. Beck, one of the founders of

cognitive-behavioral therapy, published a similar study in 1962, which,

although it found psychiatric agreement a bit higher, at between 32

percent and 42 percent, still left doubts regarding the reliability of a

psychiatric diagnosis in general [87].

Added to this came the Rosenhan experiment, a

well-known probe into the validity of psychiatric diagnosis conducted by

Stanford University psychologist David Rosenhan [88].

Published in Science and entitled "On Being Sane in Insane Places,”

Rosenhan's study consisted of two parts. The first involved the use of

mentally healthy associates or fake patients, who briefly pretended

auditory hallucinations in an attempt to gain admission to twelve

different psychiatric hospitals in five different US states. All of

these mentally healthy persons were admitted and diagnosed with

psychiatric disorders. All were also forced to admit they had mental

illness and to take antipsychotic drugs as a condition for their

release.

Figure 13

The second part of Rosenhan's experiment involved asking staff at a

psychiatric hospital to detect fake patients in a group of people who

were all mentally ill. No fake patients were sent to various psychiatric

institutions in this phase of the Rosenhan experiment, yet staffs at

these institutions falsely identified large numbers of actual mental

patients as pretenders.

The study was considered an important and influential

criticism of psychiatric diagnosis. Rosenhan concluded, "It is

clear that we cannot distinguish the sane from the insane in

psychiatric hospitals.” The study also illustrated the dangers of

depersonalization and theme re-slapping on of a label that goes

on in these institutions.

As a result of such intrusions, the American

Psychiatric Association (APA) in 1973 asked psychiatrist Robert Spitzer

to chair a classification task force to establish more precise medically

oriented parameters. The problem was that such a classification would

still be symptom or syndrome focused. The end result was a

classification manual, along the lines of Emil Kraepelin's rejuvenated

categorizing, entitled the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders (DSM), Third Edition, or DSM- III [89].

Though DSM-III was indeed more reliable than its predecessors, it still

offered no clear definition of the cause of the many different "mental

illnesses” it defined [90].

Without causes, the mere categorizing of psychiatric diseases did not

mean that they were valid to begin with and not the result of direct

physical illness. While the APA admitted it had no idea of what caused

its manual's supposed "mental” illnesses; at the same time, it felt

completely confident in its ability to diagnose and "treat” them.

Paul McHugh, former chair of psychiatry at Johns

Hopkins, noticed that the DSM has "permitted groups of "experts” with a

bias to propose the existence of conditions without anything more than a

definition and a check list of symptoms." This is just how witches used

to be identified.”[91] he noted.

Johns Hopkins Department of Pathology, 1949

Rich knew of numerous cases in which the human

placenta was infected in tuberculous mothers and readily admitted that

infection could easily pass from mother to fetus. But it was in the

frequency that he could find the disease reaching fetal tissue, limited

by the diagnostic capabilities of his time that Rich would have to speak

of TB's transfer from the placenta to the fetus as "rare.” William

Henry Welch, who besides being a pathologist like Rich was also a

bacteriologist, never would have agreed.

Welch was already on record that the mere in ability

to pick up TB in the fetus or newborn wasn't an argument against

frequent transmission to them [92].

There were just too many factors involved, such as the hostile,

low-oxygen environment of fetal blood, which could tame even the most

virulent TB bacilli into dormant forms for some time, making diagnosis

difficult to impossible.

It wasn't only Welch who Rich put himself at odds

with German investigator Baumgarten saw infection of the fetus by the

spores of TB coming from the maternal placenta as a common occurrence [93].

In fact, to Baum gar ten, who held's way over European thinking for

some time, all tuberculosis, including neuro tuberculosis, was most

commonly acquired in the womb, in utero, in most cases-though there

remained the possibility that it could occur through infected sperm-all

be it a much less significant possibility.

Ophuls mentioned that it was a well-established fact

that the semen of tuberculous men contains tubercle bacilli, even in the

absence of genital TB [94].

It was obvious, then, that the ovum from which the fetus will develop

could also become infected. Kobrinsky cites Sitzenfrey as having

"demonstrated the presence of bacilli in the interior of the ovum while

still within the Graafian follicle.” [79]

Friedmann, carefully studying the possibility in rabbits, concluded:

"It should be regarded as proved that tubercle bacilli can enter the

fertilized egg-cell, that the latter does not perish as a result of the

invasion, but may develop into a well-formed animal. In addition, the

bacilli transmitted in this way may still be present in certain organs

of the newborn” [95] and among these organs were obviously the brain and the central nervous system.

That tuberculosis is a sexually transmitted disease

is a certainty. By 1972, Rolland wrote Genital Tuberculosis: A Forgotten

Disease? [96]

And in 1979, Gondzik and Jasiewicz showed that, even in the laboratory,

genitally infected tubercular male guinea pigs could infect healthy

females through their semen by a ratio of one in six or 17 percent [97].

This prompted Gondzik to warn his patients that not only was

tuberculosis a sexually transmitted disease but also the necessity of

the application of suitable contraceptives, such as condoms, to avoid

it. Gondzik and Jasiewicz's statistics are chilling, their findings

significant. Even at syphilis's most infectious stage, successful

transmission in humans was possible in only 30 percent of contacts.

Since Gondzik, many other investigators have confirmed the potential for

TB's sexual genito-urinary transmission.

On the other hand, Schmorl's work supported

Baumgarten's and Welch's contention of routine tubercular transmission

to the fetus through the placenta. Schmorl's work again showed that,

indeed, tuberculous infection of the placenta in tuberculous mothers was

much more common than for merely believed [98].

But perhaps all of this work was up staged by Leon Charles Albert Calmette at the Institut Pasteur.

Institute Pasteur, Paris, France, February 1933

Figure 14

Calmette was on to something. He had confirmed that TB's attack form

going through the virtual filters of the placenta into fetal blood were

viral, filter-passing forms of tuberculosis. Such forms were not being

picked up by Rich's traditional TB stains or cultures. Nevertheless,

they were responsible for wasting and death, even while traversing a

perfectly normal placenta [99,100].

In going against the grain of scientific research

such as that done by Pasteur's Leon Charles Albert Calmette, Johns

Hopkins Rich, for all his authority and stature regarding the

pathogenesis of tuberculosis, was skating on thin ice. Since its

founding on June 4, 1887, the Institute Pasteur, for over a century, was

be a confer research. HIV, tuberculosis, polio, and the plague had all

been probed. In addition, since 1908, eight Pasteur scientists had

received the Nobel Prize for medicine. It was while working at Pasteur

that Calmette developed the world's first-and, to this day,

only-recognized vaccine for tuberculosis, the BCG. He was a force to be

reckoned with[101].

Calmette was fully aware of the void that Robert

Koch, the discoverer of tuberculosis, had left for future scientists

such as Arnold Rich. Koch had done it on purpose. A confirmed

monomorphist, Koch insisted that the TB bacilli had only one form that

caused disease. Extremely influential, Koch moved to make certain that

his operatives kept this view as the one most scientists to this day

have adapted.

Figure 15

Koch knew better. Bacteria and myco bacteria certainly could have more

than one form. With Arm Quist, Koch had observed different forms of

typhoid in the blood of its victims. Nevertheless, Koch would now begin

an intensive campaign to seize and rule the scientific and lay mind that

"legitimate” tuberculosis only assumed one form. Thus,

Brock points out that, despite the fact that Koch was a first- rate

researcher, a keen observer, and an in genious technical innovator, he

went from an "eager amateur” country doctor to "an imperious and author

it areas father figure whose influence on bacteriology and medicine was

so strong as to bed own right dangerous”[101].

And nowhere, according to Brock, was Koch a more dangerous and

"opinionated tyrant” than in his rigid insistence on monomorphism, the

idea that microbes could assume one truly infectious form and one form

only. Yet Klebs, who personally examined Koch's own tubercular cultures,

wrote otherwise [102].

In addition to the traditional rods of TB in Koch's culture plates,

spherical forms were regularly found, as well as branching, slender

filamentous, and granular forms. Many of these could pass a filter and

therefore could be interpreted as being 'filter able viruses'. But all

of them could revert back and become classical tuberculosis.

Koch's one-form rigidity wasn't making him friends.

There was wide spread opposition from those who sensed his lack of

evidence. They gravitated toward the more realistic, better- documented

theories of Nageli and Maxvon Petten kofer, which showed that bacteria

change forms as they evolve. Nageli and vonPetten kofer's views retained

wide support almost to the turn of the twentieth century. Koch

reflexively opposed Nageli's ideas as soon as he heard them. Much of

Koch's clash with Louis Pasteur was also based on Pasteur's discovery of

variability among microbes. In that's cuffle, mentions Brock, Koch

could at times be so personally vicious as to be shocking.

Vicious or not, by 1939, bacteriologists Vera and

Rettgerof Yale openly contradicted Koch. Vera: "The single point on

which all investigators have agreed is that the Koch bacillus does not

always manifest itself in the classical rod shape. While at times and

most commonly the organism appears as a granular rod, coccoid bodies,

filaments and clubs are not rare” [103].

To marginalize such thought, Koch and his followers,

to this day, have banished all forms, except one, into the waste basket

hinter land of "involutional” or "degenerative” forms of tuberculosis

and the mycobacteria. Forms other than TB's classic rod shape didn't

count-no matter how many studies showed that all of these forms could

regenerate to the classical TB rod, Koch and his minions thus somehow

prevailed. To Brock, Koch and his cohorts, up to today, represent a

prime instance of the excessive influence of a "cult of personality.”

The problem was that someone somewhere down the line would have to pay

for such cult-generated ignorance.

Let it be said to their credit that, from the onset,

the French saw right through Koch. Tuberculosis had many forms,

including a filterable viral-like stage in its growth cycle. Although

Fontes was the first to document these, MacJunkin, Calmette, and others

soon followed [104,105].

Again and again, either cultures or extracts of organs from tuberculous

victims, after thorough filtration through Chamber lain L2 filters,

produced tuberculosis when injected into experimental animals. And,

importantly, such forms passed right through the placenta from mother to

fetus. In Calmette's eyes, Koch's own postulates were proving him

wrong.

Some animals injected with viral, filter-passing TB

appeared normal during the time of observation, but when tested with

tuberculin showed positive tuberculin skin tests beginning approximately

twenty-five days after being injected with tubercular tissue or

microbes. Other animals lost weight rapidly And some died of a rapid

progressive infection. It all depended upon the virulence of the strain

of filterable TB being used [106].

In a series of twenty-one infants born to tuberculous women, Calmette,

along with Valtis and Lacomme, concluded that their observations proved

the frequent transmission of tuberculosis from the mother to the fetus

by means of filterable forms of tuberculosis. At the same time, Calmette

established that such viral forms of tuberculosis were in the spinal

fluid of perinatal meningitis [99].

It would take time until main stream microbiology

would be forced to even acknowledge such viral forms. It would take a

Nobel nominee by the name of Lida Holmes Matt man.

Pathology Lab of Arnoldrich, Johns Hopkins, Baltimore, 1950

A struggle was going inside the mind of Arnold Rich,

and its implications would affect Western medicine for decades to come.

Under variations in the forms TB can assume, Rich's words don't always

match his conclusions. He conceded that depending upon the type of

culture plate that tuberculosis is incubated on, the shape of the

organism changes, partly because of the culture medium and partly

because of the age of the culture itself. Even the conditions under

which this growth occurred, such as temperature and amount of oxygen,

figured in. He emphasized that non-acid fast staining rods may be

present, especially in young cultures, where as in older cultures and

infected tissues, "beaded forms” were common. Koch also had noticed

these beaded forms. Somewhat granular and protruding from stalks, Koch

thought they were potential "spores” through which infection could be

propagated. But Koch was unable to observe the granules break off into

separate segments.

Hans Much, on the other hand, for decades, not only

watched the granules break off (Much's granules) but regenerate into

classical TB bacilli [107].

Much was also able to document that the granules weren't always

"acid-fast” when stained, a hall mark for classical TB which resisted

de-colorization by acids during staining. Perhaps this was why Much's

granules were not recognized as the spores of tuberculosis that would,

with time, again become the acid-fast staining TB bacilli

microbiologists looked for.

Then there was M.C. Kahn's work. Kahn, using ideal

technique, described, in the most precise manner, his direct

observations of the growth of minute filter-passing granular forms of TB

into fully developed and virulent bacilli, capable of independent

proliferation and producing progressive tuberculosis [108].

Whether granular or otherwise, such viral-like or

cell- wall-deficient (CWD) forms of tuberculosis, often mistaken for

mycoplasma, are today widely known as "L-forms, "named after the Lister

Institute by one of its scientists, Emmy Kliene Berger [109].

L-forms are cell-wall-deficient by virtue of a breech in their cell

wall that allows them the plasticity to assume other forms, including

granular forms. Little recognized in Rich's time, L-forms of

tuberculosis have since even been found in breast milk [110].

Rich, working in the 1940s, wanted to believe very

much in these viral forms of tuberculosis. They explained the many times

that he knew he was dealing with tuberculosis but could not, even as a

pathologist, see the germ. Nevertheless, this knowledge, relatively new

at the time, was not substantiated enough. After all, Kahn had observed

the transformation of granular forms to mature bacilli in vitro in a

culture plate. This did not mean to Rich that every TB bacilli once in

humans had to go through this same cycle in its reproduction. So,

despite Kahn directly assuring him by personal communique that he had

solidified his findings in vivo in laboratory animals, Rich was not

ready to acknowledge granular viral cell-deficient forms of

tuberculosis, which were key to the mystery of how certain forms of TB