Beyond the Surface of Consumer-Staff Relationships-Juniper Publishers

JUNIPER PUBLISHERS-OPEN ACCESS JOURNAL OF INTELLECTUAL & DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

Introduction

Individuals diagnosed with an intellectual disability (ID) demonstrate higher rates of challenging behaviors (CB) than do the general population [1-3]. The literature shows that environmental factors, including negative interactions with others, can contribute to CBs [4-6]. In their thematic analysis of 17 articles on the perspectives of consumers with CBs, Griffith, Hutchinson, and Hastings (2013) found that environmental factors such as “imbalances of power, “experiences of restrictive procedures”, and “impersonal attitudes of support staff” were “accumulative stressors of living in a residential placement” that potentially perpetuated CBs (p. 469). The authors described the “Cycle of Challenging Behaviors” (p. 482) where environments containing consumer-staff relationship imbalances potentially triggered individuals to engage in CBs, which lead to restrictive procedures; these interventions increased the individuals’ dissatisfaction, creating more power imbalances and cyclical patterns that elicited more CBs.

The cycle described by Griffith [7] appeared to highlight transactional relationships between consumers and staff. Linehan [8] defines a transactional relationship as one where “individual functioning and environmental conditions are mutually and continuously interactive, reciprocal, and interdependent”, continually adapting and bi-directionally influencing each other (p. 39). Furthermore, Linehan’s bio-social theory describes how emotional and behavioral dysregulation (i.e. CBs) are created and maintained within transactional relationships between vulnerable individuals and invalidating environments [8]. These negative transactions can “shape and reinforce extreme and coercive behaviors in each other. In turn, these coercive behaviors further exacerbate the invalidating and coercive system, leading to more, not fewer, dysfunctional behaviors within the entire system” [8]. Understanding transactional processes and patterns within consumer-staff relationships may help support providers foster positive versus negative transactions.

There is a wealth of literature studying the experiences and perspectives of staff that support individuals with CBs, but far less has been written from the perspective of individuals who display CB about their relationships with their paid staff, and how the consumer-staff relationships can prevent or trigger CBs. Given the likely transactional nature of CBs, it is essential that the perceptions of consumers about their staff and support environments be central in research aimed at understanding and ultimately reducing CBs. Staff play a vital role in individual lives, potentially offering supports that prevent CBs and conversely contributing to cycles of behavioral deregulation.

Context of analysis

The current paper emerged from a broader qualitative constructivist grounded theory (CTG) study that used focus groups to explore consumers’ perceptions about their relationships [9]. The original study included 30 individuals diagnosed with ID (moderate or mild), at least one mental health diagnosis, and histories of CBs (e.g., aggression, self-injury, sexual offending, and arson) who participated in five, 90-minute focus groups. The participants were current or former clients receiving psychotherapy services at the clinical office/research site. The disclosures about consumer-staff relationships were deemed a salient topic in the focus group interviews that warranted a more focused analysis.

Methods

Constructivist grounded theory

A qualitative design was chosen for this study because it is suited well to the examination of complex, intangible, emotionally charged, abstract, and subjective topics, such as consumer-staff relationships [10]. CGT was used because its mechanisms allow a deeper empirical understanding of complex, co-constructed processes within consumer-staff relationships that may be involved in averting or contributing to CBs. CGT methods (i.e., memo writing, theoretical sampling, initial, focused, and theoretical coding) were used [11]. The research team engaged in memo writing while reviewing the transcript. Researchers wrote memos related to (1) the consumers’ perspectives; (2) the consumer-staff relationships, and (3) their own experiences/knowledgebase relative to the information. In addition, because of the subjective nature and complexity of consumer-staff relationships, it was necessary for the research team to collaborate in data collection and coding decisions to ensure that interpretations were founded.

Participants

The participants were between the ages of 24-67 (M=39.5). Twenty-five were male and five female. Twenty-two participants were White and the remaining six were visual minorities. Twenty of the participants were diagnosed with mild ID and 10 had moderate severity ID.

Recruitment

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for the study and current analysis. The purposive sample was obtained from an outpatient clinic in an eastern state of the United States. Inclusion criteria for this study included participants who: (1) were diagnosed with a mild or moderate ID, and (2) received support services through the state’s disabilities agency. Thirtyfive individuals diagnosed with mild/moderate ID that the agency served were invited, and 30 participated in this study. Two declined to participate, and three others were excluded because of either acute health or behavioral regulation problems at the time of the study that posed excessive risk. All participants had at least one mental health diagnosis, histories of CBs, and received individual and group therapy to enhance their ability to self-regulate. Twenty-nine participants were supported by eight different private residential providers with 24/7 staff supports; one individual resided in a community living arrangement with one contracted support person.

Informed consent

Prior to the focus groups, each of the participants met individually with the lead researcher/facilitator, who reviewed the informed consent with them. Prior to the focus group, participants were told that the discussion would be related to “relationships.” Each participant received a $20 gift card as compensation for his/her time. The logistical procedures were consistent across all groups. Only the age ranges are reported; pseudonyms were used to protect the confidentiality of the participants and staff.

Data Collection

The focus groups were held during a one-month period with six participants attending each group. The groups were conducted in a small conference room at the clinical office. A clinician at the agency, who also was the lead researcher, facilitated all groups. The facilitator was the individual therapist for three of the participants, as well as, conducted group therapy that several of the participants attended at various times during the courses of their treatments. All thirty participants answered a specific question about their perceptions about their relationships with staff. One participant offered perceptions about staff in response to a general question about relationships. Two participants’s shared their perspectives about staff when asked about a complicated relationship in their lives. The focus group interviews were recorded digitally and the audio files were transcribed verbatim. The facilitator reviewed the transcripts for accuracy. The research team reviewed and discussed the corrected transcripts.

Results

Initial and focused coding

During the initial coding references made by participants about people who worked with them on their residential and/or vocational teams were coded as “consumer-staff relationships”. The term “staff” included direct support professionals, case managers, and administrators associated with their residential and vocational services. Health care professionals were not labeled as staff. Positive and negative processes within consumer-staff relationships were the first categories that emerged during focused coding. Twenty-two participants described positive processes. Positive processes were when the consumers reported having experiences that led to favorable outcomes, affection, safety, respect, and satisfaction. Seventeen participants shared comments that were coded as negative processes. These described dissatisfaction, and conflicts, and a lack of favorable outcomes.

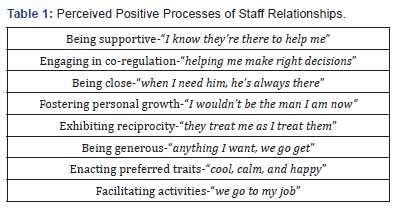

Properties of positive processes

The research team identified eight properties within the positive processes (Table 1). Being Supportive—“I know they’re there to help me.”It appeared that participants perceived interactions with staff as positive when the staff helped them actively. Logistical support and intangible, emotional support appeared to have positive influences, as well as favorable behavioral outcomes.

For example, Steve, in his late 20’s, spoke about the relationship he has with his house manager

“So, he brought me to a Chinese buffet, and we had our first date, me and my girlfriend… He didn’t have to do that. But he chose to do that.”

Debbie, in her mid-30’s, expressed gratitude about the support her vocational coordinator and case manager offer.

“I do have some staff people that are very good to me. Cory and Melissa, if I didn’t have them two, I don’t know where I would be.”

Engaging in co-regulation—“Helping me make the right decision.”Consumers appeared to be grateful for staff that were available to collaborate with them to regulate emotions and behaviors. The research team used the term co-regulation to label processes in which staff was described as offering scaffolding, passively and/or actively, that helped the consumer modulate emotions [12]. This appeared to increase connection and trust when staff members offered timely adaptive coping support proactively and during times of stress.

“If I’m having a problem with staff, he tells me to call him. So, I have a real close relationship with him.”

Similarly, Debbie stated,

“My thoughts, uh, I like the staff I work with. We get along good. If I have an issue, I go to them.”

Being close—“When I need him, he’s always there.”Participants spoke positively about relationships with staff that included an enhanced connection that bridged from strictly professional rapport to a more personal relationship. Gary, in his mid-20’s, described the way in which a staff member “…lets me call him a nickname.”

Virginia, in her mid-60’s, spoke about a close relationship she had with a former staff member, describing her as being a “best friend” and experiencing feelings of loss when she no longer worked with her

Roger, in his mid-30’s, described his relationship with a former house manager:

Gail: “It’s like a big brother?”Roger: “No, he was like—he was like a father figure to me.”

Roger: “No, he was like—he was like a father figure to me.”

Fostering personal growth—“I wouldn’t be the man I am now.” It appeared that consumers felt a deep sense of gratitude to certain key staff who had affected his/her personal development. Roger, who described his former house manager in the previous section, expounded:

“Like, I did a lot of stuff—he helped me out a lot. He helped me out a lot, really a lot. I wouldn’t be the—I wouldn’t be—I wouldn’t be the man I am now.”

Similarly, Cliff, in his early 40’s, described that he tended to exhibit CBs when he experienced higher levels of fear. It appeared that over time, he developed trust with his staff to which he attributed his changed behavior.

Cliff: “What I mean is, when I got to my program, I used to be a—actually, a full-blown ass…I didn’t care what people said, or did, I went ‘off’ for almost every day...over the years, I just calmed down and got used to the people around me. I know that they’re there to help me, and not to, um, hurt me. And I just changed.”

Exhibiting reciprocity—“They treat me as I treat them.” Relationships that appeared to be collaborative or bi-directional tended to be viewed positively. Mario, in his early 50’s, described his favorite staff member as follows:

“I have a good relationship with this staff named Pedro. We get along really good. Sometimes we go to Dunkin Donuts together; we never give each other a hard time. I think he’s number one staff for me, and he never is selfish with me.”

Marvin, in his mid-30’s, talked about the way in which the staffs’ actions and his are connected; he noted that “respect” is an ingredient for a positive transaction between them.

“I was about to say that I get along with my staff very well, because they treat me as I treat them. Because when I treat them as a human being, they—and they treat me with respect. I treat them as a human being with respect.”

Being generous—“Anything we want, we go to get. ”Participants appeared to appreciate it when staff expressed generosity by giving in tangible and intangible ways. For example, participants appreciated small gestures, such as “She brought me a free cookie, I have—when I worked with her before.” It appeared that participants described staff that was responsive to their needs in positive ways. “I have a nice lady, her name is Cindy, and she’s so sweet to us. Anything we want, we go to get.” When staff acted from the goodness of their hearts, it was viewed commonly as generosity of spirit and going aboveand- beyond the mandates of the job.

Exhibiting preferred traits—“Cool, calm, and happy.”Participants expressed positivity about staff that was able to do their jobs and be nice about it, being attentive, yet easy-going, engaging, yet flexible. Wayne described his staff as “supportive” and “appreciative.”

Andy, in his mid-30’s, commented that he liked staff that were “cool, calm, and happy.”

Facilitating activities—“We go to my job.” Participants appeared to appreciate it when staff helped them get to, and manage, preferred and necessary activities successfully. Brett, in his early 50’s, shared his sentiments about a favorite staff member who took him to work regularly

“And, uh, one good staff, he’s very good with me. We go to my job. I do janitor work. And I have a lot of fun with this person. I enjoy it.”

Properties of negative processes

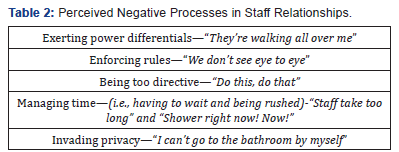

The research team identified six properties when they explored the negative processes (Table 2).

Exerting power differentials—“They’re walking over me.” It appeared that when consumers perceived that staff used power to control them, it elicited a negative response. Carlos, in his late 20’s, discussed that he perceives that his team exerts excessive control in his daily decisions. Unlike in the previous section, where being a father figure was positive; Carlos highlighted the opposing perspective that the staff hindered his autonomy, as a parent would do to a child.

“I feel that—that they’re—they’re walking over me. Like, taking advantage of me, making my own decisions, and who I want to see, sometimes, I just tell them you’re not my father or mother.”

Enforcing rules—“We don’t see eye-to-eye.” The way in which consumers and staff navigated program rules appeared to affect the consumers’ perceptions of the staff. Carlos continued to discuss the tension that arises when his team restricts his access to a potential love interest, and indicated that there are increasing levels of conflict if the team does so. He described the way in which he escalates to engaging in threats to elope.

“Um, now they’re trying to, stop me or seeing the person, and I told them, and—you stop my seeing my girl, this—this would be the last time you would see my face.”

Harry described not liking house rules related to mandated chores, and the CBs he demonstrated in response.

“I don’t want to do my chores no more, I’m getting, and I’m getting tired. I hit the walls all the time. I swear at the wall. I kick the wall.”

Being too directive—“Do this, does that.” Staff who used tones of voice and non-verbal communications that communicate demands appeared to elicit negative appraisals on the part of consumers. Paul, in his late 30’s, explained,

“Staff gets on my nerves. They tell me what to do. It’s not good.”

Arnold, in his mid-20’s, stated,

“Staff I don’t like, they’re mean, strict, and rude.”

Sean, in his late 30’s, said, “(Staff name), and he’s bossy too. And it’s not cool. I talked to him about it. I don’t feel safe with him.”

Danny, in his early 40’s, stated in a down-trodden tone,

“Like, ‘Take your meds, do your chores,’ do this, do that. It’s like—it’s like they tell you what to do—twenty four hours a day, seven days a week.”

Managing time—“Staff take too long’ and ‘Shower right now! Now!” Both having to wait excessively for staff and being rushed increased frustrations. Ray, in his early 50’s, described waiting for staff and the lack of trust that engenders.

“I never get along with them. And, she told me, I have to wait five minutes. I said, ‘I don’t want to be late for this meeting.’ I don’t want to be late—I don’t trust in her anymore.”

Conversely, participants indicated that they often felt rushed to complete tasks. Robert, in his mid-50’s, expressed his frustration with feeling rushed,

“I get home, they’re, like, ‘Go take your shower right now! Now!’…‘Come on, come on, come on, come and eat now!”

Invading privacy—“I can’t go to the bathroom by myself.” Participants complained about not having ample privacy and control over their daily activities. Carlos discussed his responses when his team restricted his phone access.

“It’s like saying—you can’t even talk on the phone without, uh, anybody else listening to your conversation.”

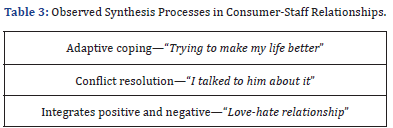

Properties of synthesis processes

During the focus coding phase the research team noticed that in approximately half of the instances when there were negative comments made about staff, the consumers also made positive statements either about the staff, themselves, and/or the overall situation. The term “synthesis” was used because a synthesis between two polarized positions can reconcile the differences and create a more congruous state. Sixteen participants demonstrated synthesis processes. Table 3 present three “synthesis processes” that participants used to reconcile polarizing situations.

Adaptive coping—“Trying to make my life better.” When the consumer experienced frustration, yet engaged in adaptive coping behavior, s/he appeared to perceive consumer-staff relationships as positive. Mel, in his late 40’s, discussed stress that he experienced that morning related to getting to the focus group on time.

Mel: “Sometimes¬—one of my staff is late this morning. We had to wait. And I got used of it— Bob, the supervisor said we had to wait till the next staff person comes in.”

Facilitator: “How was that?”

Mel: “I was nervous this morning. I called my nerves down. Uh, walk, walk outside, and get some fresh air.”

Mel labeled his emotion, which is an effective emotion regulation strategy [13,14]. Further, Mel used the coping strategy of “attention deployment” when he chose not to focus on the stimulus that triggered his escalation in emotions [13]. Mel also engaged in an activity (“walk outside, get some fresh air”) that served as a “response modulation” strategy to help him regulate his emotions [13].

Roger described stress and using adaptive coping strategies in dealing with his relationship with his agency’s director. He uses the “cognitive change” strategy of “reappraisal” (i.e., changing from a negative to positive appraisal of the stressful situation) multiple times in this excerpt; “reappraisal” (versus suppression) is an effective strategy to regulate emotion [13].

“I’m trying to work on a better relationship with my director—me and her really don’t see eye-to-eye. But I do my best with situations—and try to trust people—try to trust them more, and try to give them the benefit of the doubt.”

Conflict resolution—“I talked to him about it.” When consumers engaged in behaviors designed to resolve conflict, consumer-staff relationships appeared to be more positive. Roger described engaging in problem solving with staff to fix an incorrect contingency they placed him.

“I said, ‘You’ve got to read it again.’ They read it again, and they said to me, ‘I’m sorry’.”

Brett, in his early 50’s, described engaging in triangulation and receiving feedback from his team. He reflected about needing to collaborate with staff instead

“I have thoughts about staff that—give me feedback. I’m not do in’ so well with them…I got to work with, not to do that—but try to get along.”

Integrates positive and negative—“Love-hate relationship”. When consumers integrated and accepted both positive and negative aspects of staff, consumer-staff relationships appeared to be positive, despite the element of negativity. Walt, in his early 40’s, shared his perceptions about support staff.

“Sometimes it can be a love-hate relationship. I pretty much get along with all the staff. If I got a problem with a staff member, I express myself to them about it.”

Andy, in his mid-30’s, expressed divergent thoughts about staff, and tends to reconcile both positive and negative aspects in a way that demonstrates empathy for staff.

“Some staff is helpful to me. Some staff likes to be tough on me. But it’s their job. I know how it feels to be staff at times; working long hours and stuff, and it’s tough.”

Discussion

In this study adults with dual-diagnosis and CBs describe both positive and negative aspects of consumer-staff relationships. Positive processes (i.e., being supportive, being close, fostering personal growth, exhibiting reciprocity, being generous, exhibiting preferred traits, and facilitating activities) appeared to elicit expressions of connection, trust, and fulfillment. Consumers seemed to experience frustration when they perceived the staff engaging in negative processes (i.e., exerting power differentials, being directive, time management [delaying and/or rushing], and invading privacy). Interestingly, in approximately half of the instances when participants disclosed negative processes, they countered the adversity with positively-reframed perspectives about the staff, themselves, and/or the situation.

This third category, synthesis processes, (i.e., adaptive coping, conflict resolution, and integrates positive and negative perspectives), appeared to foster acceptance and empathy, rather than negativity in challenging situations. If the consumers engaged in synthesis processes, the trajectory appeared to enhance positive perspectives or shift negative to positive perspectives about consumer-staff relationships. Negative processes without synthesis, appeared to include disclosures of increased, unresolved frustration and descriptions of threatening or engaging in CBs. The negative transactions in this study appeared to include similar factors, such as consumers experiencing a lack of control, disrespectful/over-controlling staff, and stressed support environments noted by Griffith et al. [7]. Transactions between negative environmental factors and consumers’, who are emotionally vulnerable exhibit CBs, potentially exacerbate conditions, reinforcing behavioral deregulation, and increasing the polarization within consumerstaff relationships.

The less positive and regulated the environment is, the more vulnerable consumers will be triggered. By looking at the processes within consumer-staff relationships we can begin to understand power imbalances; more importantly, is how we create balances of power. This analysis highlights five impact points that may increase the likelihood of positive transactions within consumer-staff relationships. Training and supervising staff to (1) engage in positive processes and (2) avoid negative processes may be important preliminary steps. Third, training staff to engage in synthesis processes may be beneficial. Teaching staff coping effectively resolve conflicts and minimize polarization in stressful situations, may help the staff (a) engage in adaptive self-regulation and (b) offer effective co-regulation to consumers. Forth, offering consumers training in synthesis processes and in-vivo coaching opportunities to increase generalization of adaptive coping skills, may increase the consumers’ abilities to self-regulate, co-regulate, and mobilize self-determination [15]. Fifth, teaching consumers to address situations when negative processes happen will help decrease vulnerabilities and accountability in the environment. Conflict-free environments may not be possible, but creating environments that promote awareness, acceptance, collaboration, and growth, that are oppression-free, may reduce CBs.

Conclusion

This analysis highlighted the dynamic nature of consumerstaff relationships and examined bi-directional processes that may avert or contribute to CBs. Awareness of these factors may help consumers and those who support them to avoid oversimplifying solutions and encourage the ample allocation of resources to address the challenges that exist within consumerstaff relationships.

Limitations

This was a relatively small study conducted in one region in the eastern United States with a clinical population. Although this specialized sample allowed us to collect rich data related to individuals with ID, mental health issues, and CBs, the small sample size reduces the ability to generalize the findings. The fact that the facilitator had existing therapeutic relationships can be considered a limitation. The facilitator’s dual-role may have influenced the level of adaptive coping that consumer’s articulated. The fact that all of the participants engaged in therapeutic interventions that were designed to improve selfregulation, may have increased the likelihood of disclosures that contained evidence of emotion regulation skills. Alternatively, the enhanced relationships may have offered the unique opportunities that fosters rich data collection that may have not been accessible within less familiar relationships. It is important to note that CGT assumes that there is co-creation of research; the CGT methodologies are designed to manage and optimize empirical data collection and analyses.

For more Open Access Journals in Juniper Publishers please click on: https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/juniper-publishers

For more articles in Open Access Global Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disabilities please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/gjidd/index.php

For more Open Access Journals please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com

To know more about Juniper Publishers please click on: https://juniperpublishers.business.site/

Comments

Post a Comment